PIVOTING

Every device that communicates with/across a network needs an IP Address. Usually this is done automatically via DHCP server, but it is possible to statically assign an IP address to a network device. Static IP addresses are common with servers, printers, routers, switch virtual interfaces, and other critical devices on the network. Each IP address is assigned to a Network Interface Card (NIC) or Network Adapter.

Lets say you have been tasked with testing an internal network and ultimately compromising the domain controller, but you can’t reach any of the IP addresses in scope from your attack machine/server. The most common solution here is to use a Virtual Private Network (VPN). A VPN is a sort of point-to-point tunnel established between your computer and a remote server that encrypts your personal data and masks your IP address. Common uses of VPNs include getting around location restrictions, accessing office networks remotely, or sidestepping firewalls, ACLs, or other website blocks. If you’re familiar with sites like HackTheBox, a VPN is often used to connect to the networks that house the training materials or the target machine. In our case, we could use a VPN to get access to the target internal network by establishing an encrypted tunnel between our attack machine and a device that does have access to the internal network.

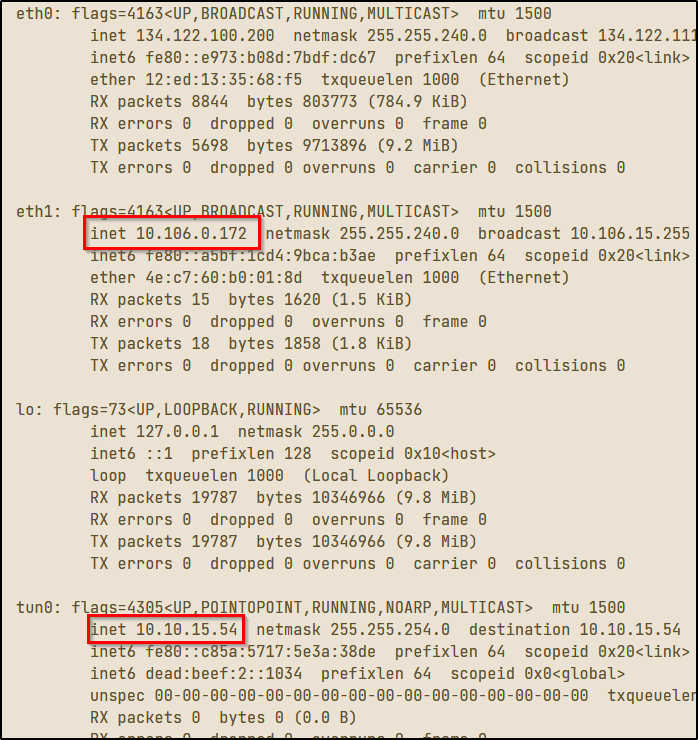

This technique is called pivoting, and it is a vital skill to master. Pivoting is a technique in which an attacker uses a compromised system to access other systems within the network. Lets look back at our example above. Say the client wants you to do an external penetration test, which just means you are attacking from outside of the network. In this situation, your attack machine still does not have direct access to the network, but maybe we can find a server or device that does have access to the internal network. During your information gathering phase, you discover that the client has a website that anyone can access from the internet. After some subdomain/directory enumeration, you are able to find a subdomain that consists of ad admin or mail login page. From my (admittedly limited) experience, this will often be the case. Lets say you are able to brute force this login page and discover an IT/Help Desk email account that contains a saved draft with login credentials, along with an SSH private key. Using these credentials, you are able to access the command line interface (CLI) for the external facing web server. You start to get a lay of the land and run the command ifconfig:

In the image above, you can see that each Network Interface Card (NIC) has a label or identifier that goes with it. The tunnel interface (tun0) indicates a VPN connection. This will be the IP address of the externally facing web server we gained access to. The (lo) interface is the localhost/loopback address and the (eth0) interface is the IP that is publicly routable, meaning the ISP will route any traffic from this IP address across the internet. The (eth1) interface is what we’re interested in here. You can see that both the VPN IP and the (eth1) IP address begin with 10, which means both addresses are in the same subnet that can be represented as 10.0.0.0/8. This is the CIDR notation for all class A private IP addresses from 10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255. Since this machine is dual-homed, or connected to two different networks or subnets, we can use this machine to access the 10.106.0.0/16 subnet that we could not previously access from our attack machine.

Pivoting is an example of lateral movement, or moving laterally through a network until we are able to escalate privilege and move vertically. You will be unable to run any scans or attacks directly against the 10.106.0.0/16 network, but there are techniques we can use to route traffic through our pivot host to attack our target directly. I’m going to discuss two of those methods – tunneling and port forwarding.

PORT FORWARDING

We could just SSH into our compromised machine and run any commands from there, but this presents a few problems. For starters, many tools require sudo (root/admin) privileges to run. This can be a problem with something like our compromised web server as we will not always have root access. If we are trying to be stealthy, we don’t want to transfer a ton of tools to the server and run a bunch of resource consuming scans to find avenues for privilege escalation, if those avenues even exist. We need a way we can use our own attack machine against the internal network, somehow going through the compromised web server. One method of doing this is called port forwarding. Port forwarding is a technique in which traffic is routed from one designated port to another

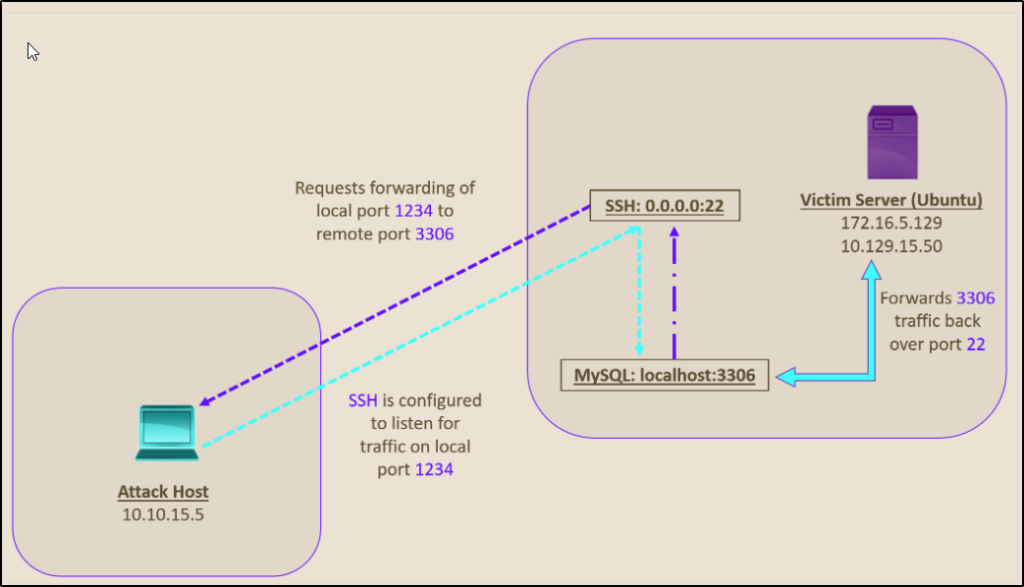

In the image above (taken from HackTheBox.com), we are connecting to the web server via SSH on port 22, and we are trying to access the MySQL server on port 3306 of the target server. Instead of connecting to the web server via SSH and accessing MySQL from there, we can set up a port forward to send all traffic from the remote port 3306 to our localhost on port 1234. This will allow us to execute a remote exploit on the MySQL server. Since the MySQL server is hosted locally on the target server on port 3306, we would not be able to run any exploits without port forwarding.

We can set up the local port forward with the following command

# ssh -L 1234:localhost:3306 ubuntu@10.129.15.50The -L tells the SSH server to forward all the data sent from our local port 1234 to the localhost:3306 on the target server. You can confirm the port forward was set up properly using the command -> netstat -antp | grep 1234

You should now be able to run nmap or any other scans on the target host through port 1234. You can also set up multiple port forwards in this way by adding more -L commands.

# ssh -L 1234:localhost:3306 -L 8080:localhost:80 ubuntu@10.129.15.50SSH TUNNELING

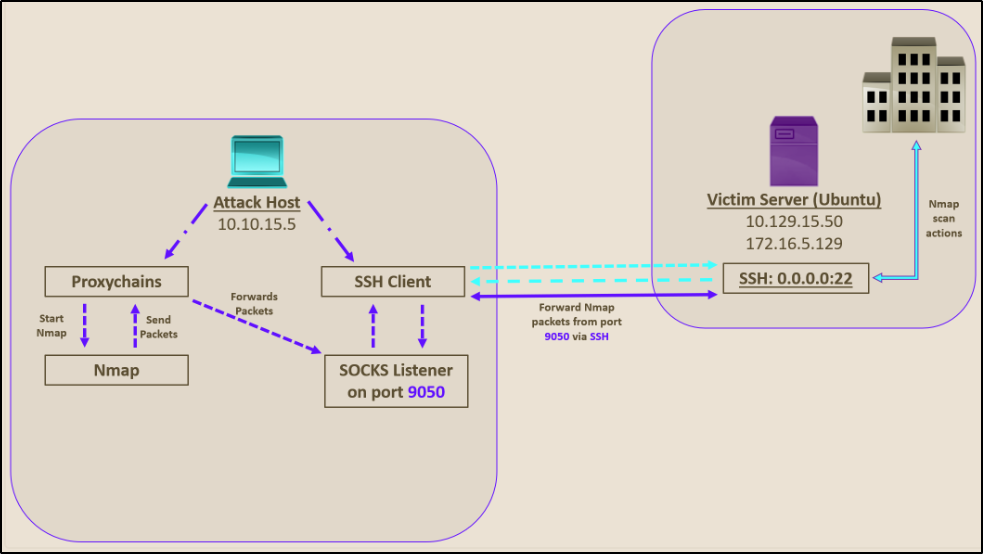

There will be situations where we, as the attacker, do not know which services are in use on the other side of the network and we don’t have a specific port to target. We’d have to scan the network to find out which services are in use, but as with before, we cannot do the scan directly from our attack host since we have no route to the internal network. To get around this, we can set up dynamic port forwarding to pivot our packets to the target server. One way to do this is by starting a SOCKS listener on our local attack machine and then configure SSH to forward all traffic via SSH to the target network. SOCKS stands for Socket Secure, which is a protocol that helps communicate with servers through a firewall or external SSH server. This method of dynamic port forwarding over SOCKS proxy is called SSH tunneling.

This technique of SSH tunneling over a SOCKS proxy is a good way to get around firewall restrictions and access areas that were once protected by a firewall. When making a connection this way, the initial traffic is generated by a SOCKS client, which connects to a SOCKS server that we (the attacker) control. Once that connection is established, network traffic can be routed through the SOCKS server and can pivot to an internal or external server. There are two types of SOCKS proxy – SOCKS4 and SOCKS5. The main difference between the two is that SOCKS4 does not provide authentication and UDP support, whereas SOCKS5 does.

To enable this dynamic port forwarding with SSH, we can use the following command.

# ssh -D 9050 ubuntu@10.129.15.50The -D tag will enable dynamic port forwarding over the port we specified, 9050 in this case. Once we have this enabled, we will need a tool that can route any packets over the port we selected. One way to do this is via a tool called proxychains. Proxychains is a tool that is capable of redirecting TCP connections through TOR, SOCKS, and HTTP/HTTPS proxy servers. We can also use proxychains to, as the name implies, chain multiple proxy servers together. Using this method has the added benefit of hiding the IP address of the requesting (attack) host. Any monitoring on the receiving host will only see the IP of the pivot host, which is the web server in our first example.

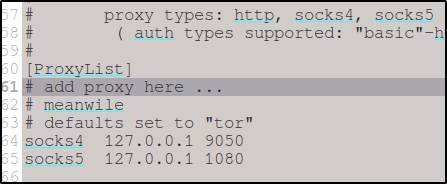

Before we can start forwarding traffic, we must inform proxychains of the port we intend to use. To do this, we must modify the proxychains configuration file located at /etc/proxychains.conf.

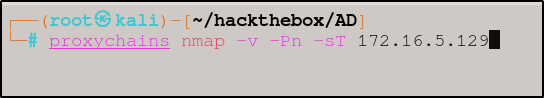

Now that we have everything set up, we can dynamically forward traffic by prefacing each command with proxychains.

From here, you can use any command you need to for further enumeration. If you need to use metasploit, for example, you would start metasploit with the command -> # proxychains msfconsole

SSH PIVOTING with SSHUTTLE

There exists a ton of tools out there that can help simplify the pivoting/tunneling process, including Chisel, Rpivot, Netsh, Socat, and even DNS tunneling with dnscat2. I will provide a link to those, but my preferred method is using a tool called sshuttle.

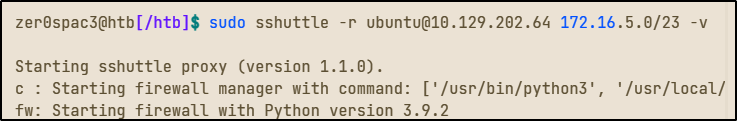

Sshuttle is a tool written in python that eliminates the need to configure and use proxychains. It only works over SSH, but it is extremely useful for automation and pivoting, largely because it eliminates the need to preface commands with proxychains. Once you install sshuttle (sudo apt-get install sshuttle), we run the command to specify our pivot server as well as the network or IP we want to route through.

Once we have set up sshuttle, we can now run commands as usual without the need to preface each command, so long as you keep the sshuttle terminal open. This is my preferred method as it is a kind of set it and forget it, and I am very prone to forget it. The downside of sshuttle is that it only works over SSH and does not provide ways to pivot over TOR or HTTPS proxy servers like proxychains does.

This post just barely scratches the surface of pivoting, tunneling, and port forwarding. I am by no means an expert, I’m just trying to provide an overview of the things I learn as I learn them. Pivoting is a vital skill for any penetration tester or ethical hacker. Engagements are not always as simple as just connecting to a VPN or attacking the target network directly. Hopefully these methods will get you started on discovering what works for you, and it probably won’t be the same as what works for me. There’s about a dozen ways to do everything, and tools come and go, so it is important to understand the methodology behind these techniques and why they are important.

Happy hacking

– z[r3d4ct3d]

[All images courtesy of HackTheBox.com]

![[+] – zer0space.html – [+]](http://zer0space.me/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/zzz.png)