When I was in college around ’08 – ’09, I stumbled my way into becoming a freelance web designer. Like most millennials, I learned the basics of coding largely through MySpace and AngelFire. Pages would play your favorite emo song when people visited with fireworks or pink sparkles falling down the screen like glitter. You could find templates around the web, but most sites were made with pretty basic HTML and CSS. I was working my receptionist job at Wolfram Research when my boss, Maggie, asked if I could run the website for her lesbian choir group. Being the outspoken young lesbian I was, I jumped at the opportunity. That was my first experience with content management systems, Drupal. It used to be that you’d upload your site files via FTP and designate a folder in Windows as a place to sync up with the web server. Needless to say, I had no idea what I was doing. I’m a pretty quick learner, so I managed to get something going for them, but I could only procrastinate so long before they decided to go with someone else.

I honestly can’t remember how, but I managed to meet up with a man whose name I have forgotten who owned a graphic design business called DreamScape Designs. He hired me to do a website for a local painting company at $10, and that’s how I accidentally stumbled my way into being a freelance web designer. At the time, most basic websites were written in a combination of HTML and CSS. Over the next couple of years, more and more websites started using Java and/or JavaScript, which I didn’t know how to do. That was the end of my web design career. It was a weird time in my life, so I never did end up learning JavaScript.

JavaScript is a client-side programming language used to add interactive elements like dynamically updated content, multimedia, animated images, button clicks, form validation, and any other animated or interactive elements you can think of. In 2025, JavaScript is a core technology on the web and is used by about 98.8% of all websites. As with any new technology, more advance tech means more advanced vulnerabilities. One such vulnerability is called Cross-Site Scripting (XSS).

CROSS-SITE SCRIPTING (XSS)

A typical web application works by receiving HTML code from the back-end server and rendering it on the client side. If a site does not properly sanitize user input, say on a contact form, we can take advantage of that vulnerability by entering some code into the form. We can execute JavaScript code on the client-side to capture cookies or log in data, change the appearance of a web page, or even create fake login pages.

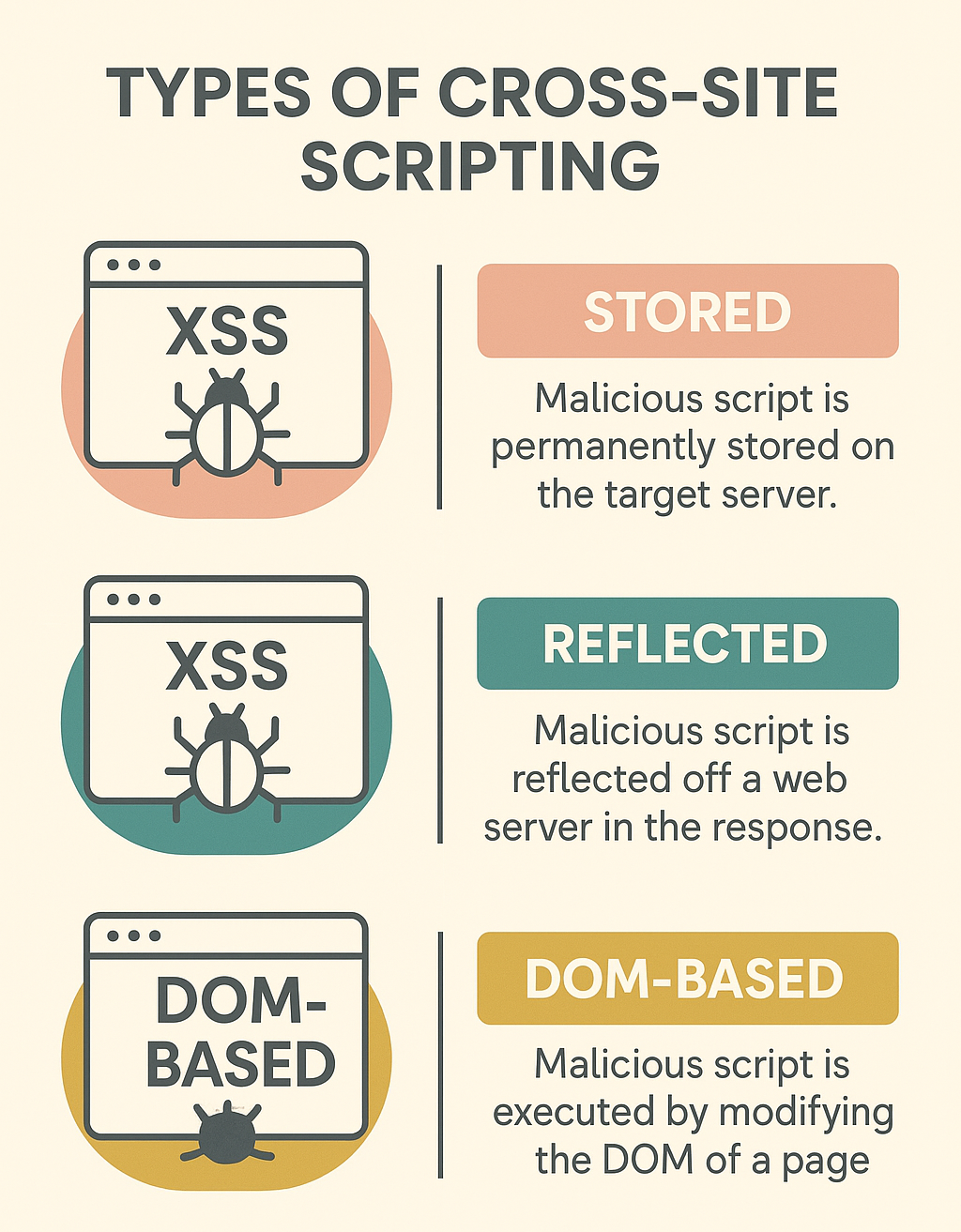

There are three different types of XSS vulnerabilities that we must understand before learning how to use and identify XSS vulnerabilities.

- The first, and most critical, type is Stored XSS, sometimes called Persistent XSS. Stored XSS happens when the payload we inject gets stored on the back-end server or database, which means that the malicious script will be run when any user visits the site. This is the most critical type of XSS because it affects a wider audience and is often very difficult to get rid of.

- Reflected XSS vulnerabilities occur when our input is processed on the back-end and returned to us without any sanitization. Reflected XSS vulnerabilities are non-persistent, meaning they will not carry over to other pages or users.

- DOM-based XSS vulnerabilities are completely processed on the client-side via JavaScript. DOM XSS occurs when JavaScript is used to change the page source through the Document Object Model (DOM). This is also a non-persistent vulnerability.

XSS vulnerabilities are executed solely on the client-side and do not change the back-end server.

STORED XSS

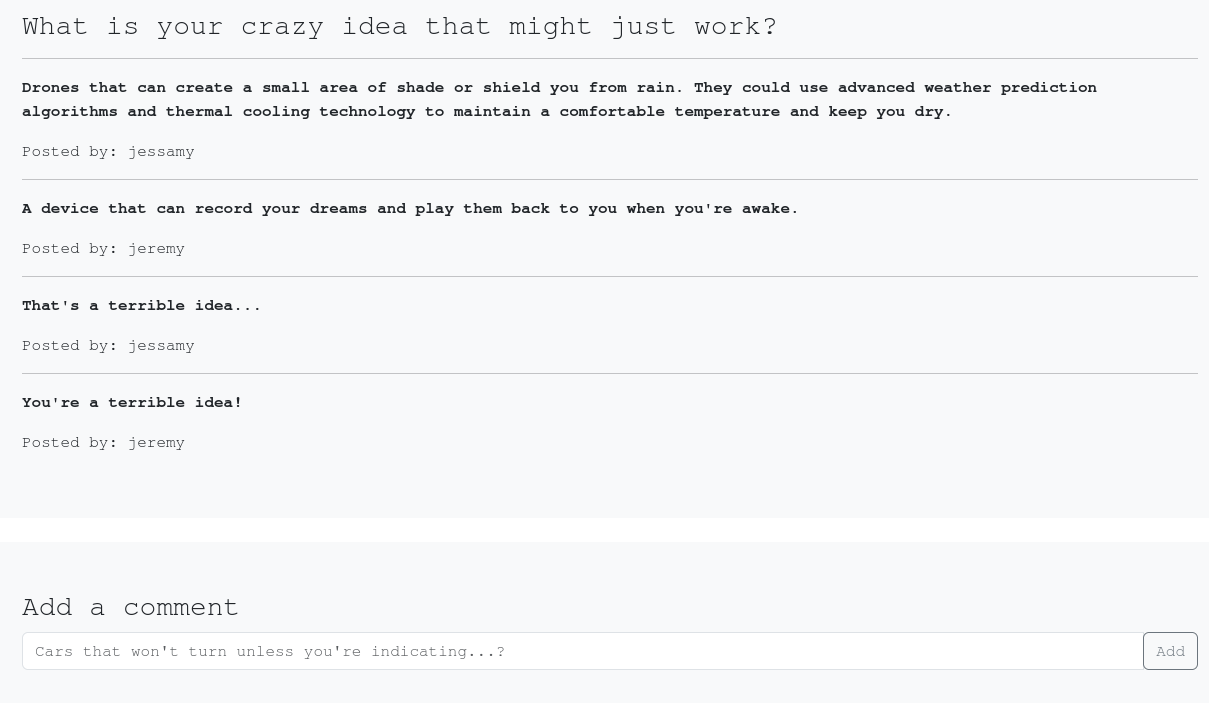

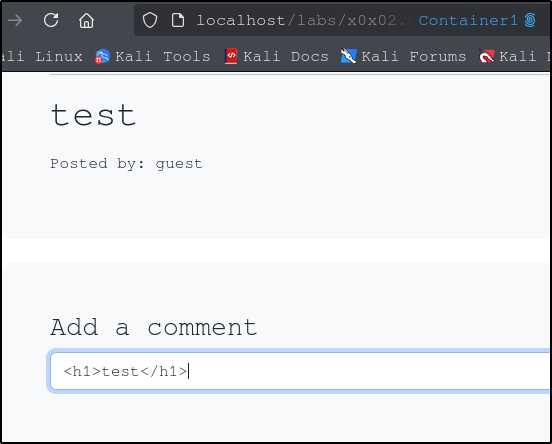

Lets look at the website above. It looks like we have a reddit type clone of the subreddit r/mightJustWork. We see the question at the top with some fun answers, then a text input at the bottom where we can submit our own crazy idea. To try to determine whether this site is vulnerable, lets try entering a basic HTML header script using the <h1> tag. If we type <h1>test</h1> and submit, we see the text posted like before, but the size has grown to the size of a heading. If we open the page in two different containers, we can see that the heading script has persisted across multiple users.

Beautiful. So we know that we are able execute at least some code, which will be stored and executed for anyone who visits the website. This type of code injection is one thing hackers will use to deface a website by changing colors, backgrounds, text, and images. It may even be possible to inject code that will grab malicious code or malware from an external source and execute that code each time the page is visited.

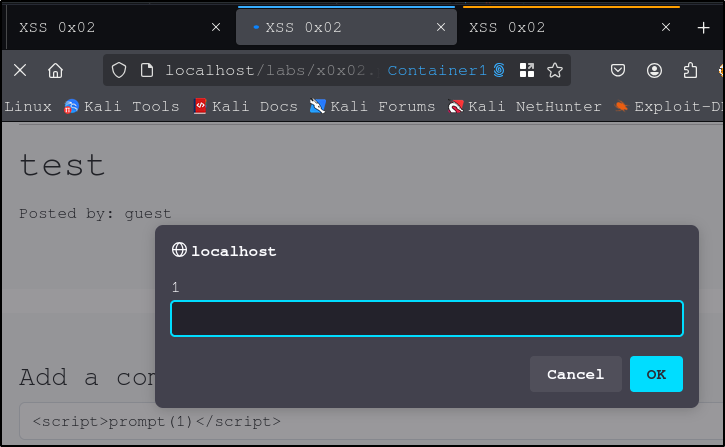

We can also inject some JavaScript. Using the ‘prompt’ command, we can create a pop up prompt each time the page loads.

<script>prompt(1)</script>

Since this is a stored XSS vulnerability, the prompt will appear for each user who visits the site.

REFLECTED XSS

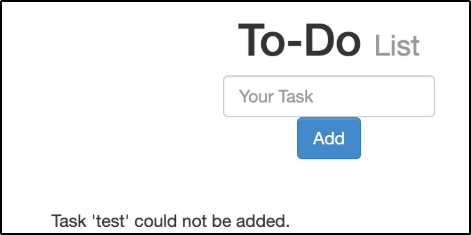

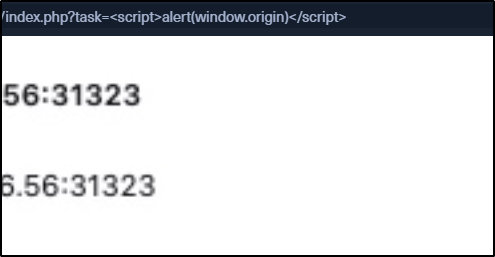

In this case we have a to-do list with a text input. If we submit a test input, we can see that our input is reflected back on the page in single quotes. It looks like our input is not being sanitized at all, just reflected. Lets try some JavaScript code to see if we can execute some scripts.

<script>alert(window.origin)</script>

It looks like our script was executed successfully. If we look at the source code, we can see that it does contain our script. The text inside the <script> tag is rendered by the browser, so if we look at the spot where were the input was reflected back to us, we see there is nothing inside the single quotes. Once we refresh the page, our script goes away. This is what is meant by non-persistent.

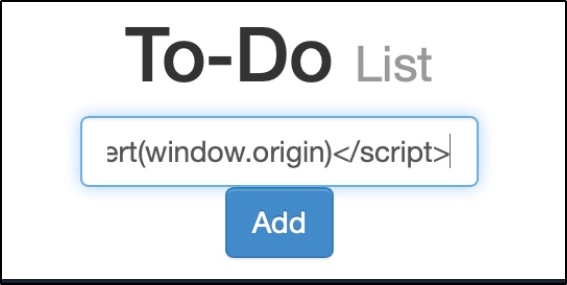

This type of vulnerability seems innocuous, but there are ways of targeting a specific user. Lets check which kind of HTTP request we are sending by opening the Developer Tools in Firefox (CTRL + Shift + I) and clicking on the Network tab, then submitting our test payload. There we can see our payload with a GET request. GET requests send their parameters and data via the URL.

In the image above, we can see the specific file/URL for the GET request. The payload (‘test’) is included in the page URL after the ‘index.php?task=’.

If we add the alert(window.origin) script after the = we can see that the command was executed. To target a specific user, just input your script and copy the URL to send to your target. The script is not stored anywhere, but rather executed from the browser of anyone who uses that link.

DOM-BASED XSS

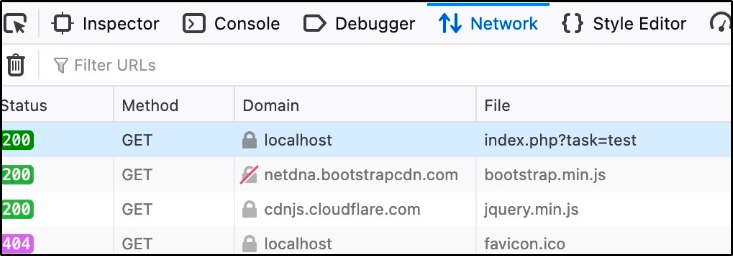

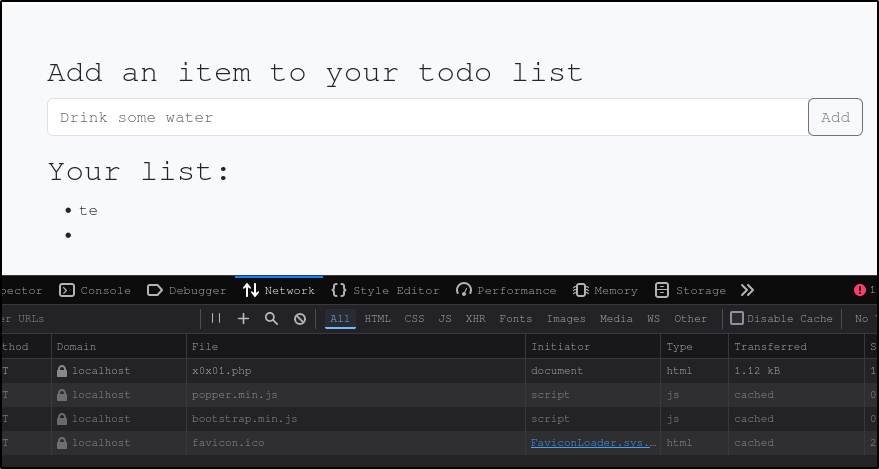

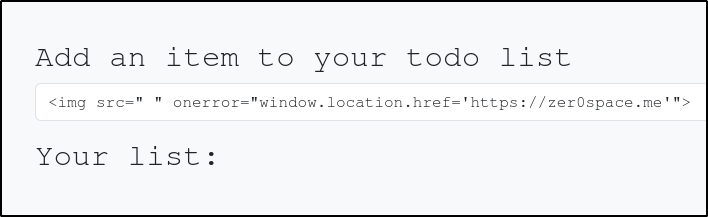

The final type of XSS vulnerability is called DOM-based XSS. While reflected XSS send the input to the back-end server through HTTP requests, DOM XSS is processed completely on the client-side using JavaScript and occurs when JavaScript is used to change the page source through the Document Object Model (DOM). In the image above we see a to-do list, a text input, and a button to submit. If we look in the Network tab of the Developer Tools console we see that our test input does not come with an HTTP request, which means our payload is not getting sent to the back-end server.

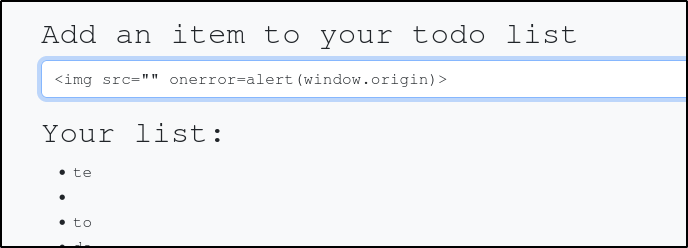

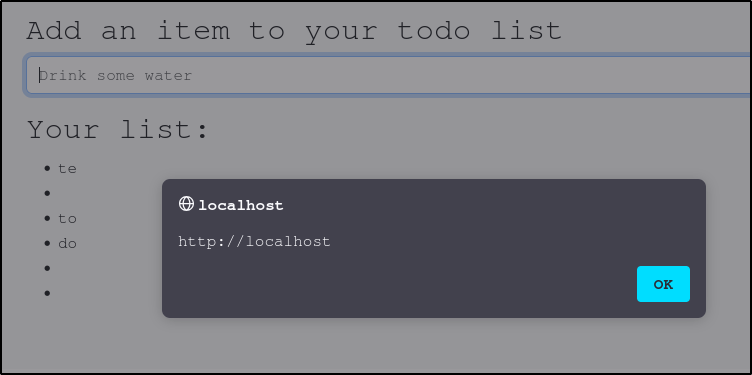

So far, we have been using simple alerts and prompts in JavaScript. For this site, we will not be able to use any of those payloads because the innerHTML function does not allow use of <script> tags as a safety precaution. Fortunately, there’s a ton of other payloads we can use. You can find a list of payloads on PortSwigger or from this xss-payload-list GitHub page. We are going to try the following payload: <img src=”” onerror=alert(window.origin)>

This script will create an image object with an empty source. When the browser looks for the image and fails to find it, the ‘onerror’ attribute tells the browser to load an alert containing the address for that page. You can use DOM XSS with the <img> attribute to execute all sorts of commands. One thing we can do is redirect the user to another website that we control using the following command:

To further understand DOM-based XSS, we need to understand the concept of the Source and Sink. The Source is the JavaScript object that takes the user input, which can be any input parameter like a URL parameter or an input field. The Sink is the function that writes the user input to a DOM Object on the page. If the Sink function doesn’t properly sanitize the input, it will be vulnerable to an XSS attack. Some of the commonly used JavaScript functions to write to DOM objects are: document.write(), DOM.innerHTML, DOM.outerHTML.

FINDING XSS VULNERABILITIES

As XSS vulnerabilities become more common, so too do the tools we can use to detect them. Most web vulnerability applications (Burp Pro, Nessus, ZAP) have the capabilities to detect all three types of vulnerabilities. A Passive Scan reviews client-side code for potential DOM-based vulnerabilities, while an Active Scan sends various types of payloads in an attempt to trigger an XSS. Paid tools like BurpSuite Pro are usually going to be a lot faster, but there are plenty of free options available. Most of the tools work by identifying input fields on a web page, sending various payloads, and comparing the rendered page source to see if the payload can be found. If so, that indicates the page may be vulnerable to XSS. Some common XSS tools are XSStrike, BruteXSS, and XXSer.

The simplest, and most time consuming, way to discovery XSS vulnerabilities is to try a handful of payloads. You can find huge lists of XSS payloads online, such as PayloadsAllTheThings and PayloadBox. That being said, no one wants to copy/paste hundreds of potential payloads just in case one of them might work. Automated tools can help here. If the three tools above do not suite your needs, it may be more efficient to write your own Python code to further automate the discovery process.

![[+] – zer0space.html – [+]](http://zer0space.me/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/zzz.png)